The first phase of the research to identify the location of the house of Gillis van Coninxloo and propose a reconstruction hypothesis has been charted in this previous blog post. Further research has confirmed its location and added details to the appearance of this house and the evolution of this part of the Oude Turfmarkt over time. This blog post summarizes some of the main findings.

Frans Badens’ house

Due to the temporal proximity between Coninxloo’s death and the purchase of a house on the Turfmarkt by painter Frans Badens (Fig. 1) from Arent ten Grootenhuys, Badens’ house has been identified as the most likely candidate for Coninxloo’s.1 His house was just north of the narrow alley that is visible on the map of Amsterdam made by Balthasar Florisz. van Berckenrode in 1625 (see the previous blog post). The likelihood that Badens took over the house where previously Coninxloo lived is increased by the fact that in the tax registrations (‘verponding’) of 1647-49 and 1650-52 Baden’s house is the only one that is taxed for 200 guldens, the same amount that Coninxloo had to pay to Ten Grootenhuys for a month of rent (as recorded in Coninxloo’s inventory).2 Other archival sources, most notably transport acts, contain additional pieces of information on some of the house’s characteristics and informs us about the people who lived in this and neighbouring houses over time.

The house of Gillis van Coninxloo at the Oude Turfmarkt: New insights

The first phase of the research to identify the location of the house of Gillis van Coninxloo and propose a reconstruction hypothesis has been charted in this previous blog post. Further research has confirmed its location and added details to the appearance of this house and the evolution of this part of the Oude Turfmarkt over time. This blog post summarizes some of the main findings.

Frans Badens’ house

Due to the temporal proximity between Coninxloo’s death and the purchase of a house on the Turfmarkt by painter Frans Badens (Fig. 1) from Arent ten Grootenhuys, Badens’ house has been identified as the most likely candidate for Coninxloo’s.1 His house was just north of the narrow alley that is visible on the map of Amsterdam made by Balthasar Florisz. van Berckenrode in 1625 (see the previous blog post). The likelihood that Badens took over the house where previously Coninxloo lived is increased by the fact that in the tax registrations (‘verponding’) of 1647-49 and 1650-52 Baden’s house is the only one that is taxed for 200 guldens, the same amount that Coninxloo had to pay to Ten Grootenhuys for a month of rent (as recorded in Coninxloo’s inventory).2 Other archival sources, most notably transport acts, contain additional pieces of information on some of the house’s characteristics and informs us about the people who lived in this and neighbouring houses over time.

Fig. 1: Frans Badens in the Pictorum Aliquot Celebrium Praecipuae Germaniae Inferioris Effigies (source)

‘Het huijs van den Iteliaen’ and its ‘gemene gangh’

For example, we know that Coninxloo’s house had a wall and a lead gutter shared with its northern neighbour and that the narrow alley was shared (‘gemene gangh’) with the southern neighbouring house.3 As we learn from the sources, this alley was primarily used to remove rainwater (‘osendrop’) and allowed access to the small courtyard of the southern neighbour situated at the back of the house.4 The archaeological excavations carried out by the Amsterdam Municipality and cited in the previous blogpost shed light on the measurements of this narrow space, about 1 meter wide. From another archival document drawn up at the end of the century we also know of the presence of windows and a door on the side of the house which opened onto the shared alley.5 Although this document refers to the situation in place decades after Coninxloo lived in this house, we can reasonably expect that a door and a few windows would have existed also in Coninxloo’s time on the side of the house bordering the shared alley.

A particularly interesting source is a schematic plan of this house’s southern neighbour made in 1648 and kept in the archive of the Gasthuis (Fig. 2).6 The plan maps out the inner division of its southern neighbour in detail and shows that the shared alley allowed access to the back of this house. It also shows how the kitchen was built against the slanting wall of the Nieuwe Nonnenklooster. Although the house where Coninxloo once lived is rendered only with its perimeter, the representation of space of its southern neighbour (especially the shape of the courtyard and the kitchen in the back) offers us a visual source to hypothesize a similar situation at the house where Coninxloo’s once lived. As the note written within the perimeter of the house tells us, at this time this was ‘the house of the Italian’ (‘het huijs van den Iteliaen’). The existence of the tax registration for this year allows us to identify this Italian man with Filippo Biancucci, a merchant from Livorno.7

Fig. 2: The plan made in 1648 of the house neigbouring the shared alley to the south (right in the image). The house to the left of the shared alley is the house where Coninxloo once lived and is now defined as ‘het huijs van den Iteliaen’, the merchant Filippo Biancucci (Amsterdam City Archives, 342 Inventaris van het Archief van de Gasthuizen, inv. 1435).

Oude Turfmarkt over time

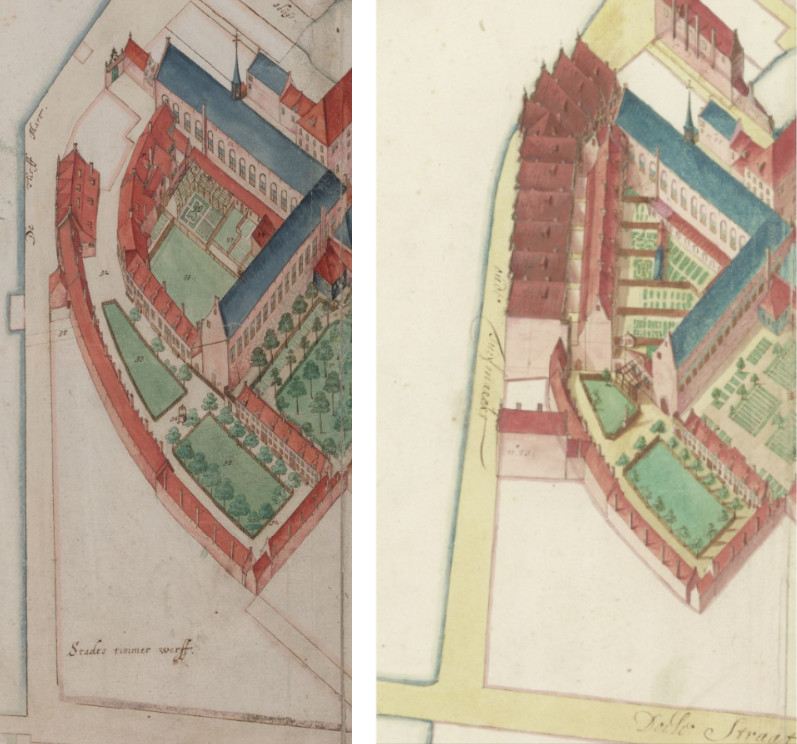

One important element to consider in order to situate the houses that Hudde built on the Oude Turfmarkt – and Coninxloo’s house among them – is the location of the entrance to the Gasthuis (which nowadays serves as the main entrance to the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam). As is clearly visible by comparing the maps of the Gasthuis made in 1628 and in 1680, the location of this entrance has changed (see fig. 3). This is a consequence of the big renovations that were carried out on the Turfmarkt in the early 1640s: The architect Philips Vingboons worked on both northern and southern ends of the street and built a series of houses with a neck-gable facade for the Pietersgasthuis, and two houses (nrs. 145-147) with a twin-facade for Pieter Jansz Sweelick. To make room for the houses built by Vingboons, part of the northern inner courtyard (nr. 93, called ‘‘t bleeck velt’ in the map captions) was removed and the entrance to the Gasthuis was moved toward the south. Being acquired in 1656, the southern neighbour of ‘Coninxloo’s house’ and the shared alley appear on the map of the Gasthuis made in 1680. Numbered 23, this house is defined as the soldiers house (‘soldaaten huys’) in the map captions. An axonometric view made in the same year shows this house viewed from its southern side with two chimneys in the main building and one in the smaller annex on the back which served as the kitchen (Fig. 4, right).

Fig. 3: Comparison between the maps made in 1628 and 1680. In the middle section, the perimeter of Vingboons’ houses is roughly superimposed on the map of 1628 to give an idea about the portion of the inner courtyard that was incorporated into the new design and the shifted location of the access to the Gasthuis terrain. (Amsterdam City Archives, 342 Inventaris van het Archief van de Gasthuizen, inv. nrs. 1468 and 1469).

Fig. 4: Axonometric maps made in 1628 (left) and 1680 (right) displaying a more detailed rendition of the Gasthuis (Amsterdam City Archives, 342 Inventaris van het Archief van de Gasthuizen, inv. nrs. 1468 and 1469).

Historical photos display the development of this part of the street in more recent times. In one of the earliest, dated 1865, the entrance to the Gasthuis is visible and the remnant of the shared alley can be glimpsed through the tree in front of the house (Fig. 5, top image, highlighted in blue). The house on the right side of the alley in this photo therefore occupied the space where Coninxloo’s house used to lie. In 1870, this house and its northern neighbour were dismantled and the Amsterdam ‘Spaarbank’ was built on their two plots. As can be seen from a picture of the Spaarbank taken around that year, the shared alley, walled up and closed by a door, is still on its place (Fig. 5, second image, highlighted in blue). The alley will remain there until 1883, when it was dismantled to build the Sint Bernardus Gesticht (Fig. 5, third and forth images).

Fig. 5: Historical images showing the evolution of this part of the street over time. Highlighted in yellow, the entrance to the Gasthuis (now the main entrance to the Allard Pierson Special Collections); in blue, what remained of the shared alley mentioned in the archival sources and uncovered by the archaeological excavations in this area. The alley was then dismantled in the late 19th century with the construction of the Sint Bernardus Gesticht (images from the Amsterdam City Archives beeldbank).

As this Coninxloo case has demonstrated, archives are a treasure trove to reconstruct the history of a house, its inhabitants, and its neighbours. Pieces of information to be cross referenced can come from disparate sources, even produced much later than the period in question. This time consuming but rewarding task of researching archival materials over a long period of time helps to shed light on the diachronic urban development and on the people that inhabited these buildings. The schematic, grey-scale 3D reconstruction of Coninxloo’s and neighbouring houses (fig. 6) based on the sources discussed in these blog posts and a chronological list of these sources are available to download from the Amsterdam Time Machine zenodo community (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7274567).

Fig. 6: The schematic 3D reconstruction of Coninxloo’s and neighbouring houses resulting from this research and available to download from the Amsterdam Time Machine zenodo community.

Acknowledgments

I thank Frans Grijzenhout and Bart Reuvekamp for their help with the archival research on this case study.

Footnotes

- Amsterdam City Archives, Archief van de Schepenen, Register van Schepenkennissen (5063), inv. nr. 11, fol. 285 (15 June 1607). See the previous blogpost with references to Dudok van Heel 1987 and Bok 2005.

- Amsterdam City Archives, Inventaris van het Archief van de Thesaurieren Extraordinaris (5044), 254-293 Verpondings-quohieren van den 8sten penning. 41 perk. (Oud nr. 33), 1647-1733, inv. nr. 254, fols. 195r-200v and inv. nr. 255, fols. 195-1v – 200v; Amsterdam City Archives, Inventaris van het Archief van de Notarissen ter Standplaats Amsterdam (5075), notary Frederik van Banchem (nr. 13), inv. nr. 262, fol. 86 (11 January 1611).

- Kwijtscheldingen, archive nr. 5066, inv. nr. 36 and Kwijtscheldingen, archive nr. 5067, inv. nr. 25 (18-06-1680).

- Ibidem.

- Kwijtscheldingen, archive nr. 5062, inv. nr. 73, 26-06-1698.

- I thank Frans Grijzenhout for finding this plan and share it with us.

- Amsterdam City Archives, Inventaris van het Archief van de Thesaurieren Extraordinaris (5044), 254-293 Verpondings-quohieren van den 8sten penning. 41 perk. (Oud nr. 33), 1647-1733, inv. nr. 254, fol. 195 and inv. nr. 255, fols. 194-2 and 195-2.